Adapted from When Helping Hurts: How to Alleviate Poverty without Hurting the Poor…and Yourself, 13-14, 16, 52-54, 64

Caring for the materially poor is not an optional aspect of the Christian life, but there is no “one-size-fits-all” recipe for how each Christian should respond to this biblical mandate.

Some are called to pursue poverty alleviation as a career, while others are called to do so as volunteers. Some are called to engage in hands-on, relational ministry, while others are better suited to support frontline workers through financial donations, prayer, and other types of support. Some Christians are called to work at a government level, seeking to promote justice for the poor through public policy. Others are called to work in the business world where they can provide job opportunities for the unemployed. Many Christians work with churches or parachurch ministries, allowing them to communicate openly the love of Jesus Christ through both words and deeds. And some Christians simply minister as individuals, walking across the street to help a neighbor in need. Each Christian has a unique set of gifts, callings, and responsibilities that influence the scope and manner in which to fulfill the call to help the poor.

We praise God for this diversity of gifts and resources in His church, but we also want to say as loudly and as clearly as we can: GET MOVING!

We believe that the coexistence of agonizing poverty and unprecedented wealth—even just within the household of faith—is an affront to the gospel. You see, what is at stake is not just the well-being of poor people—as important as that is—but rather the very authenticity of the church’s witness to the transforming power of the kingdom of God. Hence, the North American church should have a profound sense of urgency to spend ourselves “on behalf of the hungry and satisfy the needs of the oppressed” (Isa. 58:10).

What’s the Problem?

That having been said, good intentions are not enough. It is possible to hurt poor people, and ourselves, in the process of trying to help them.

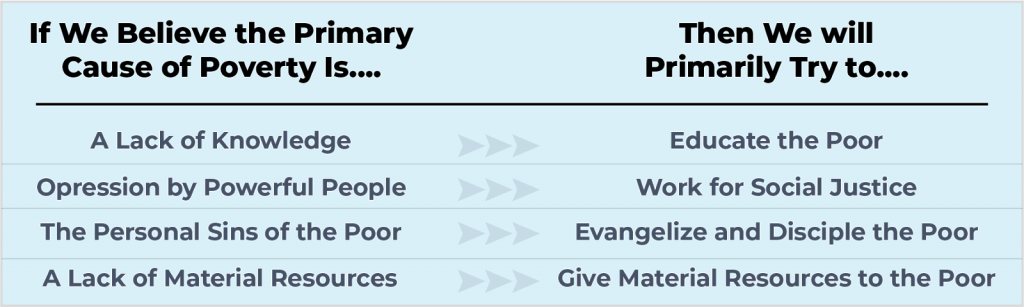

You see, how we diagnose the problem of poverty directly impacts how we will seek to address it, and many of us have not thought through the complexity of material poverty to make a good diagnosis.

We’ve asked many people over the years how they would define poverty. In the vast majority of cases, middle-to-upper-class Westerners describe poverty differently than the materially poor in lower-income communities or countries do. While people who are poor mention having a lack of material things, they tend to describe their condition in far more psychological and social terms than our North American audiences. Poor people typically talk in terms of shame, inferiority, powerlessness, humiliation, fear, hopelessness, depression, social isolation, and voicelessness. Wealthier individuals tend to emphasize a lack of material things such as food, money, clean water, medicine, housing, etc. This mismatch between many outsiders’ perceptions of poverty and the perceptions of poor people themselves can have devastating consequences for poverty alleviation efforts.

While there is a material dimension to poverty there is also a loss of meaning, purpose, and hope that plays a major role in poverty. The problem goes well beyond the material dimension, so the solutions must go beyond the material as well.

Defining poverty is not simply an academic exercise, for the way we define poverty—either implicitly or explicitly—plays a major role in determining the solutions we use in our attempts to alleviate that poverty.

Think of this example: When a sick person goes to the doctor, the doctor could make two crucial mistakes:

1) Treating symptoms instead of the underlying illness;

2) Misdiagnosing the underlying illness and prescribing the wrong medicine.

Either one of these mistakes will result in the patient not getting better and possibly getting worse.

The same is true when working to alleviate poverty. If we treat only the symptoms or if we misdiagnose the underlying problem, we will not improve the situation, and we might actually make the lives of the materially poor worse in the long run.

A sound diagnosis is absolutely critical for helping poor people without hurting them. But how can we diagnose such a complex disease? Divine wisdom is necessary. The Chalmers Center roots our understanding of poverty and its alleviation in God’s big story of creation, fall, redemption, and consummation. Although the Bible is not a textbook on poverty alleviation, it does give us valuable insights into the nature of human beings, of history, of culture, and of God to point us in the right direction.

Helping without Hurting

Consider the example of a person who comes to your church asking for help with paying an electric bill. On the surface, it appears that this person’s problem is the last row of the table above, a lack of material resources, and many churches respond by giving this person enough money to pay the electric bill. But what if this person’s fundamental problem is a mental health issue or the effects of trauma that prevent him from keeping a stable job? What if he’s been kept out of the workforce by a lack of self-discipline or the soft skills necessary to work with others? Simply giving this person money is treating the symptoms rather than the underlying disease and will enable him to continue struggling along without long-term transformation.

In this case, the gift of the money does more harm than good, and it might be better not to do anything at all than to give this handout. Really! Instead, a better—and far more costly—solution would be for your church to develop a relationship with this person, a relationship that says, “We are here to walk with you and to help you use your gifts and abilities to avoid finding yourself in this situation in the future. Let us into your life and let us work with you to determine the reason you are in this predicament.”

While the symptoms of poor people largely look the same around the world: they do not have sufficient material things (according to the varying standards we hold of what is “sufficient”), the underlying diseases behind those symptoms are not always very apparent and can differ from person to person. A trial-and-error process may be necessary before a proper diagnosis can be reached. Like all of us, poor people are not fully aware of all that is affecting their lives, and like all of us, poor people are not always completely honest with themselves or with others. And even after a sound diagnosis is made, it may take years to help people to overcome their problems.

There will likely be lots of ups and downs in the relationship. It all sounds very time-consuming, and it is. “Spending yourself in behalf of the poor” often involves much more than giving a handout to a poor person, a handout that may very well do more harm than good.

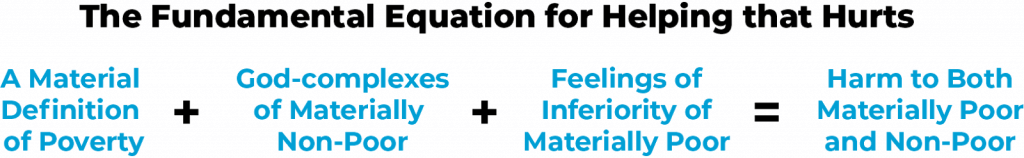

Our efforts to help the poor can hurt both them and ourselves. Often churches and nonprofits in middle-to-upper class contexts find themselves locked into the following equation:

Taking the Next Steps

What can be done to break out of this equation?

1) Changing the first term in this equation requires a revised understanding of the nature of poverty. Many Christians need to overcome the materialism of Western culture and learn to see poverty in more relational terms.

2) Changing the second term in this equation requires ongoing repentance. It requires North American Christians to understand our brokenness and to embrace the message of the cross in deep and profound ways, saying to ourselves every day: “I am not okay; and you are not okay; but Jesus can fix us both.”

3) And as we do this, God can use us to change the third term in this equation. By showing low-income people through our words, our actions, and most importantly our ears that they are people with unique gifts and abilities, we can be part of helping them to recover their sense of dignity, even as we recover from our sense of pride.

But do not let these truths paralyze you. Study. Learn. Pray. Repent. Try to do something. Evaluate, and then repent again. And then trust that a sovereign God is more than able to take our feeble acts and turn them into something that He can use for His glory. We would love for every Christian to quadruple their efforts to help the poor and do so immediately. But maybe we should also consider doing things differently than we have in the past.

Want to learn more about how to go beyond good intentions? Join us September 27 to meet Hope for San Diego affiliates and learn from Dr. Brian Fikkert, author of When Helping Hurts